STAY INFORMED

Subscribe to our mailing list to stay informed about upcoming events, training and conferences, new publications, and other Edu20/20 related events and news.

Nearly every district our team has supported this year is wrapping up the first year of a brand-new curriculum implementation. It’s been meaningful, challenging, and, at times, exhausting work. As the year winds down, our focus is shifting to helping instructional leaders reflect on progress and re-energize for the next phase of implementation, the one that drives a deeper impact for both teachers and students.

But “re-energize” can feel like a tall order when curriculum work comes with so much noise: pacing concerns, logistics, resource overwhelm, and more. It’s easy to slip into the mindset of thinking, “Next year will be better,” without a clear path for how. So the real question becomes: How can we stay strategic, stay focused, and make smart support decisions for year two implementation without drowning in the details?

Enter the Pareto Principle.

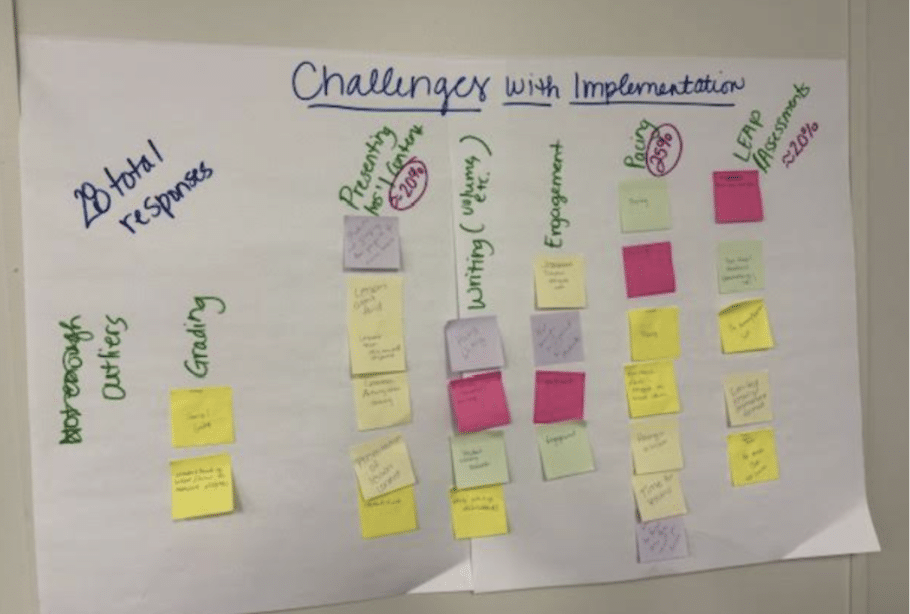

In its most simplistic form, the Pareto Principle suggests that 80% of your problems often stem from 20% of the causes. Using that principle, we hypothesized that we could drill down the information we had from initial implementation to identify a few pain points that caused some of the greatest challenges. And guess what? We were right.

Let’s look at one example from a district implementing a brand new 6-8 ELA curriculum. Here are the steps we took with 14 instructional leaders from various schools:

1. Stick It: Identify the Most Prominent Challenges

Sometimes the most effective strategies aren’t flashy—they’re sticky! We launched a little “sticky note audit” of implementation by giving each leader two sticky notes. On one, they wrote down one of the most prominent challenges they had observed with curriculum implementation. This could be from quantitative data collected or trends identified through instructional observations. On the other note, we had them write down a top challenge that they frequently heard from the teachers themselves. This qualitative data was the most critical.

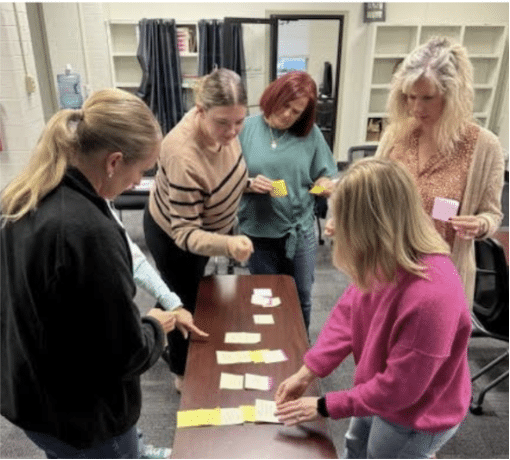

2. Sort It: Group the Sticky Notes By Common Topics

Next, we had leaders bring their sticky notes to a table in the center of the room, discuss their challenges, and then sort them into groups based on topic patterns. While this wasn’t a clean process, it actually worked out well. Leaders had to elaborate a little more about their challenges in order to group them effectively, and the discussions of what was really happening in classrooms were powerful. There were some clear, distinct patterns that emerged from the sorting activity as the team created titles for the topic categories.

3. Solve It: Identify the Top Challenges and Identify Next Steps

Not every issue held equal weight. In fact, a few repeated concerns accounted for a large part of the feedback: lesson pacing (25%) and the need for instructional moves for lesson delivery (almost 20%) were the top two contenders. There was another close category– the need for more state test-aligned assessment opportunities– but leaders felt like lesson pacing and instructional moves for lesson delivery were practical places where they could begin designing support for year two. They began looking at how they could leverage collaborative planning structures, professional learning days, and instructional coaching for these two areas.

Making Implementation Manageable

This process wasn’t surgically precise. Honestly, the first time we ever tried this was a little nerve-wracking because we couldn’t predict the outcome and it felt, well, kind of messy. Realistically, no leader is going to have all the answers for all of the issues that arise from trying to use a brand new curriculum–and that’s ok! Every single school and classroom comes with its own set of variables and challenges, but the beauty of this process is that we recognize our limitations and choose to focus on the one or two areas where we can leverage support. In other words, we make implementation manageable.

After all, there’s never going to be a “perfect curriculum.” (Sorry, not sorry, curriculum companies.) It’s always going to come down to the knowledge and skills of the teachers using the materials. This process just helps leaders strategically decide where to spend the most vital resources of time, energy, and money on areas that support teachers in building knowledge and instructional skills as they do the incredible work of teaching students.

This process is also adaptable. While it may not pinpoint a single obvious need that’s clearly above all others, it can be a great place to begin thinking about next steps.

If you give this process a try or adapt it for your own team, we’d love to hear how it goes!

Fill in your information below and select the options to request a proposal for Jill Jackson training (Part One, Part Two, or both).